The Bear

Editors Joanna Naugle and Adam Epstein share the secret ingredients that helped make — The Bear — the summer's breakout hit series. Step into the kitchen like never before.

Today on Art of the Cut, we talk to the editors of FX on Hulu’s The Bear. It’s got some really innovative editing and when I queried Art of the Cut fans about the shows they wanted to hear more about, The Bear was high on the list.

The editor of the pilot episode — and half of the others in the series — is Joanna Naugle. In addition to her work on The Bear, Joanna also has worked on TV series including Ramy, Big Mouth, Human Resources, and Some Good News.

Adam Epstein ACE’s other work includes more than a decade at Saturday Night Live, plus TV series including The Other Two, Documentary Now!, and Mr. Mayor. Short on time? Read our 6-minute best of recap.

Art of The Cut with the Editors of HULUs The Bear

I watched the first five episodes last night in a binge. What a great and very interesting show. Tell me a little bit about how you got involved with this series and what your marching orders were.

NAUGLE: I cut the pilot last summer, and it all goes back to Josh Senior, who started Senior Post. I started working with him around 2012 when he was just opening up this post house. We were renting office space and I was basically the first editor he hired and now — cut to 10 years later — I’m a co-owner of Senior Post and he's executive producing scripted shows and comedy specials. So this was the first TV show he was able to executive produce. We had previously worked with Christopher Storer on Ramy and a couple of other comedy specials.

The stars aligned, and Chris was making the show; he knew he wanted to work with us, so he brought Josh on as an EP and me as the editor of the pilot. Then it was green-lit towards the end of last year, and we were wondering who our absolute favorite editor was that we wanted to add to the team, and it was Adam Epstein. So that timed up perfectly for him to join us.

EPSTEIN: That's very kind but very hyperbolic [laughs]. I am very lucky to have worked with everyone at Senior Post before, and everything went really well and really smoothly.

This show is a really good example of when timelines are tight and things are intense if you genuinely enjoy and have a really comfortable rapport with the people you're working with, it makes it so much easier to experiment and not be too precious about things and not be afraid to talk through stuff. I think that really lent itself here.

I had worked with them on a few things at Senior Post before starting with John Mulaney the Sack Lunch Bunch for Netflix and A24. I did a comedy special that Chris Storer directed. I’m very lucky they reached out, and it all timed out. It was a great process all in all.

The show has a very unique editing style, especially the pilot. I guess this is a question more for Joanna. What did the director or showrunner tell you when you started cutting that?

NAUGLE: It's so funny. In preparation for this, I looked back at the first cut that I submitted to Chris and Josh, which was almost 39 minutes long. Thinking back on that, and now it's 28 minutes, I think we cut out a full 10 minutes. When I look back, I forgot that each of the scenes at the beginning was scripted and supposed to play out in their entirety instead of this crazy montage. So I sent it to Chris and Josh and told them it’s a rough cut and very long. He said, “I feel like we need to be thrown into the world as immediately as possible.” So we basically tried to condense the first 10 minutes before all these back-to-back scenes into a three-minute montage. So initially, I cut it down to four minutes and asked, “What do you think?” and he’d say, “All right, let's get it down to three and a half.” So then we get to three and a half minutes, and he’d say, “I think we can do three minutes."

At first, we actually had some Chicago archival shots in that montage, but then we couldn't clear some of them. And it also seemed like it was a little bit too much going on. So then we started putting in family photos of the Berzatto family and actual photos of Jeremy as a kid. That's when it went to the next level for me. I just loved making it more about Carmy, introducing us to this world, and then once you're in the kitchen, he was like, “You should make people feel like they wanna turn it off. It should be overwhelming. People need to pause it and catch their breath.” I thought it was crazy, I've never edited something that's so in your face and fast, but the effect made you feel like you're right next to Richie screaming over you to Carmy and Sydney. It really was about bringing the audience into the experience. We’re not even going to explain that much, but you're going to get the vibe, and hopefully, you don't have a heart attack and still will want to watch episode two. [laughs]

We played so much with music. There are actually scenes where two different tracks are playing, and one will become louder when Carmy’s talking and louder when Richie's talking, and it's just supposed to create this feeling of who’s in charge. This is a power struggle and this is the most stressful environment you could imagine. Hopefully, for the rest of the season until episode seven, things progressively get better and better as they start to figure out their jive, but it should start from a place of “this is hell for Carmy” and just go from there.

Adam, I'm assuming that you watched that pilot before you came on?

EPSTEIN: Yeah, I remember watching it the first time and then talking with Josh and being like, “Holy shit! Is the whole show gonna be like this?” because, at the time, I hadn't read the rest of the scripts yet. I think it's incredibly cool, but I don't know if I could watch a whole season at that speed. It’s been really fascinating to see as the season developed and as we were figuring out what is the progression of the overall macro feel of the season as opposed to a scene-to-scene thing. It's really an episode-to-episode kind of thing as far as the way that the pacing, color timing, background ambiances, and even the sound effects evolve over the course of the season in a very deliberate way that I didn’t anticipate at first because they're being very smart and deliberate in the sense of it mirroring the journey of what's going on in the kitchen or what's going on internally with Carmen.

When I first saw that pilot, I thought, “Oh my God, this is nuts!” They were very smart about how they thought out the overall arc from a big-picture level.

Well, as you say, the rest of the episodes aren't like the first episode or even the first five minutes of the first episode. I absolutely loved the editing and thought it was very creative and interesting. We're talking about this firehose speed, but there are moments of release or moments for you to catch your breath.

EPSTEIN: That's one of the things that I found interesting. When people read anything about how they describe the show, they always focus initially on how intense and how fast it is. Which, part of it is, but then part of it compared to other TV is very deliberate and very slow. It's that balance between the kitchen madness, and then they literally go outside or it's a person alone, and you get that release valve which is usually a four-minute shot or, in the case of the last episode, a seven-minute monologue straight to camera.

You have these moments that are playing considerably slower and more drawn out that feel much more like you're watching theater rather than a very manufactured piece of TV, which I thought was great. It's like a Pixies song where it’s loud, then quiet, then loud, and then a breath which is a cool rhythm to find.

Any thoughts on that, Joanna, in finding those moments to release the tension?

NAUGLE: Yeah, definitely. It felt exactly like what you're saying. Finding that relief as I was cutting to let shots linger because for so long, it was us trying to figure out how to make this as fast-paced as possible. How do we create this beast that Carmy is trying to tame? One of the hardest scenes for me to cut was the opening of episode two when they're in the fancy kitchen. It was interesting because it was finding the in-between of that, where it should feel fast-paced like a kitchen, but everyone is a well-oiled machine, and it is like a symphony. I remember thinking, “Okay, how do we distinguish that this is another way to run a kitchen and that it could not be more opposite from where we're going.”

I remember we cut from that scene to Carmy at The Beef yelling at the top of his lungs and then that really long scrubbing shot. It was cool to juxtapose these two kinds of different but fast-paced work environments. To then have this really long moment showing that this is a man who's holding it together by a thread and he wants to clean the floor in this one moment and really sitting with him, building this empathy early on for this guy who clearly is very damaged and troubled.

EPSTEIN: That transition out to the call “Hands! Hands! Hands!” is one of my favorite turns in the whole series. From the gleaming white to this, the scuzzy kind of green, yellow. Ugh. Awesome. So good!

NAUGLE: During coloring, I remember Chris saying it should feel blown out. It’s like this fancy restaurant is angelic, so bright it's blinding. Then you get exactly like what Adam was saying, nothing's white in The Beef everything is dirty or oily except for maybe Carmy’s shirt, but still, that contrast should be very apparent in all aspects of it. Editing color, sound, everything.

EPSTEIN: So much of that color that you get as far as the elevated dishes in there are photos of other places as opposed to the actual place itself, which I always thought was funny. There's a sequence of a panic attack that Joanna cut that’s one of my favorite things ever because you normally think of panic attacks as madness, which it is. The other side of it uses just breathing and stills of incredibly high-end, beautiful, fine dining as almost like a calm down. The way that she balanced the images and the breath and feeling someone ramp themselves down, I thought, was incredible.

It's funny because when you're working on it, you're not really watching it as a viewer, so after it's been out, it was nice to have a little break and go back and watch everything through and be like, “Oh man, there are some parts there that are so good!”

Were you guys regularly working together, or were you almost always working apart and seeing finished edits from each other?

NAUGLE: We really stuck to our own episodes, for the most part, I'd say. But I feel like there were moments where we'd ask each other to watch a scene and see what was or wasn't working. I remember there was this one scene. Specifically, that was supposed to be in episode two: the plum scene. I feel like you and I handed that back and forth so many times because we were trying to find the right episode for it. Honestly, it was like when I was cutting the pilot by myself, I wanted someone at times to let me know if this was working or not. Somebody who knows how to manipulate a sequence in order to achieve the desired effect.

I feel like we were each other's first sounding boards, and it was so fun to have some downtime and go and see where each other was on their edits and what they were doing.

Like I love what you did with the flashes to the crawfish and the shrimp, seeing a little bit into Sydney’s interior world. That influenced how we then handled the panic attack in episode eight. There was also a lot of watching what each other was doing with the episodes, seeing how the characters are growing, and then bringing that into some of the later episodes. The way that Adam was using fades in the kitchen would inspire me to try a fade here and there because, a lot of times, that wouldn't be my first instinct, but I thought this was a cool tool to have in my arsenal.

We were creating this language, and even if we weren't always talking about it, just watching each other's cuts was a helpful way to make the kitchen feel this way or that way or a way to linger on the characters more.

EPSTEIN: What I would normally do is throw a two or three-minute-long clip up on Slack and say, “Check this out. I'm curious about either the music under here or is it better with no music?” We were on Slack a lot, talking back and forth. One of the main bummers about working from home is not having an in-person "gripe partner” to an extent. [laughs] In post-production, it is very important, not in a negative obviously, to have someone who really understands what you are going through. Oftentimes even if you're wrong, just to be able to vent and get something off your chest is so helpful. That would happen a lot in the private Slacks. It really was nice to be able to do that, which speaks to the benefits and the luck of working with people you like to work with and are friends with.

Like Joanna, I was also picking up little things from her cuts. For example, music is so important in the show, but there are moments where she is using the song, and it falls right in between. Not like a music video style, but there are moments where you're doing little tricks to do massive time jumps within the context of the music that would then make things feel a little more special than just a straight montage.

I remember there was a small moment — but it's one of my favorite parts in the whole show at the end of episode 2 — where there's this Breeders track where, at the beginning of the song, there’s a brief moment where it drops out for a second and on one side of the dropout, Carmy is starting a dish or getting something ready. In that brief moment of the pause and the track, she put in this super extreme close-up of a timer setting so the sound effect of the timer and the sound effect of a burner is going on and then cuts right back to Carmen, basically in the same position.

You've done a half-hour jump now, and there's a full chicken there. It had this cool music video vibe to it without it being a full music video set to the track. That's a little thing that I saw which made me think, “Okay, this is a cool way to go about using the music thematically.”

That's a great example. Joanna, any thoughts on building that scene?

NAUGLE: I think that was something that even Chris encouraged me to try because he and Josh Senior were so involved with choosing a lot of the tracks, too. Literally, on the pilot, he sent me a playlist of around 40 songs and said, “This is the world of The Bear. Feel free to pull from these tracks at the starting point.” Similar to how the show ended up, the music was all over the place. There was a ton of Wilco, rap, jazz, Van Morrison, and dad rock, all these different genres and movie score soundtracks. I loved that we didn’t have to stick to a certain genre. He was really in tune with the songs because he had been listening to this playlist, and it was a lot of his favorite music that ended up there.

So in that scene, he said, “Oh, there's this dropout here. Let's build up the sound.” From early on, we really spent a lot of time doing our temp sound design. It was so helpful for inhabiting the world and for a show that's so specifically about pacing. The moments that feel loud should feel really loud, and the quiet moments should feel really quiet. Kudos to our Assistant Editors, Josh Depew and Megan Mancini, for doing a lot of sound work for us. The music created the rhythm of the kitchen, and everybody operated on that same frequency in pace.

Did the two of you have a sandbox of audio full of kitchen sounds like burners and mixers?

EPSTEIN: Tons and tons of it.

NAUGLE: So much of it! We were drowning in all the different oven sounds.

EPSTEIN: Yeah, the sound effects bins by the end were pretty substantial, which should be nice for the second season as a jumping-off point, although who knows. The kitchen might be very mellow by then, and it'll just be just some running water in the back and some slow chops or something.

NAUGLE: We also had the most epic B-roll project because they did that full beef process so many times. We were using a shared project system, so if you're in the B-roll project, we had food beauty shots, kitchen beauty shots, and messy kitchen shots. They collected so much B-roll, which was great. That's not even counting the exteriors. We had so much Chicago B-roll. It was such a great resource because I remember Chris was talking about how fire should be a motif throughout. So we had so many different angles and focal lengths on fire turning on or things like that. I feel like we made use of that throughout the season and could easily cut to a cooking montage if we haven’t seen food in a while. No need for reshoots. We have like eight hours of it here. [laughs]

EPSTEIN: It was cool to be able to use montage and especially the way that they shot so many beautiful close-ups that really allowed you to get much more experimental with it, and that ended up becoming what normally would be an establishing shot. It's very rare, if ever, that we said, “Here's the exterior establishing of the restaurant, or were at the house” It's just “boom, you're in it.” It was great to have that resource to be able to design different transitions that weren't the most predictable.

There is a lot of handheld camera in this series. When the two of you are watching through dailies, how much is the performance of the camera part of your decision-making process, as opposed to the performance of the actor?

EPSTEIN: For me, it varies so much from scene to scene, especially in episode three, after the Al-Anon meeting with Molly Ringwald, and you're back in the kitchen, and it's just mayhem. Or you're back in front-of-house during the service, and everyone's screaming, everyone's overlapping each other, and it's really on top of itself. What I would do a lot of times is try to get the audio rhythm sounding right first. I could basically watch it without even looking at it and make sure that even though it's on top of everything, you can hear where everyone's coming through, the right lines are being punctuated, and then go back and do a base visual on top of that. Then go back and really focus on stuff like deliberate moves where they were trying to find Marcus on this line, for example. It was a three-step process on that, but then there were some scenes where you could see, “Oh, this was by design.” So for me, it was very contextual depending on the scene.

NAUGLE: Yeah, I'd say that I would lean more towards actor performance than camera performance in this show because we also could get away with a lot more shaky camera or if things were finding their focus. That fit into this world and it wouldn't fit in every show, especially the scenes where everyone is in the kitchen and talking over each other. Those were some of my favorite scenes to cut because there's so much going on. If there ever was a weird camera bump, it would be like, “Oh, great cut to a reaction shot of Sweeps or something.” There's so much going on, and they did a great job covering that and making you feel like you were in the room that it did seem like it was easy to cover over those things. It didn't feel like a bandaid. I think a little bit of the jitter added to a lot of the scenes and the chaos of them.

No spoilers, but episode seven was a huge camera achievement. So that was about basically choosing the right take and letting the incredible camera work shine.

I noticed claustrophobic shot sizes, especially in the pilot. Was that just good filmmaking making you feel like you're stuck in this tight kitchen, or was it the fact that it was a tight kitchen that there was no other way to shoot that?

NAUGLE: It was a little bit of art imitates reality, imitates art situation. A fun fact is that they shot the pilot in an actual kitchen, and then they rebuilt the kitchen for the actual series but didn't shoot it in a studio, and so I had to keep reminding myself, “Oh, they're not in an actual kitchen.” They did such a good job. They intentionally boxed themselves into the tight kitchen space, just from the nature of the show. The extreme closeups of the food or the faces really did lend themselves to these feelings of intensity between these characters. The moments where you see a wide of the kitchen are really chosen at very specific moments because everything felt so much more personal when you're seeing two people yell at each other in closeups, rather than it playing out in the wide.

EPSTEIN: Even that was really going from the focus of plate of food up to the hand, up to the face panning across landing somewhere else and really deliberate and still close up. The thing I liked about that, the way that they would frame so much stuff, was it kept you so isolated from anything else going on.

Someone said to me, “Are there ever customers there?” and the answer might be "sure," but they're not really thinking about that to the extent they're thinking about what is going on in the moment in this second that I have to get something done right now. This was myopia and not being able to see what's right in front of your face was a powerful device.

Talk to me about Chris Storer and the kind of creative notes that he gives you two: the collaboration that you have, what you're giving him, and what he's giving back.

NAUGLE: Chris is the most enthusiastic creator of a show I've ever worked on. He was endlessly positive. We'd send him a cut, and literally, 28 minutes after sending it, he'd say, “I just watched the cut. It looks so dope. Here are some thoughts, and I'll follow up more.” His energy is infectious because he clearly loves the show and loves the process. His sister is a chef in real life. He’s from Chicago, so I think it was a very personal story to him, and he understood the language of the restaurant really well.

That was helpful to me on the pilot. He'd say, “Oh, we should be moving faster for this. This is just another day for them.” He inhabited the world really well, but I think he was also pretty hands-off in terms of editing in a way that was really exciting as an editor. Even really specific time code notes would be, “This should feel like Carmy feels the world was closing in, and he's just thinking of Michael.” That would be a cool thing for me to process and figure out what are the things that we can do to achieve that and send it back to him.

EPSTEIN: I totally agree. It is so refreshing and such a blessing to be able to work with someone confident enough in their own vision, as far as what it should eventually be, but then also trusting enough in the people that they're working with to be more descriptive versus prescriptive in the way that they would give notes. There were never notes like “Oh at such and such time, Carmy should look left instead of right” It was always more like, “We should feel the weight more and maybe linger a little more here” The notes were usually much more about feeling and vibe than really specific dialed in notes, which was just great. It gave you the freedom to experiment, which then led to happy accidents that would end up being more interesting than anything you could have thought of.

I've had people tell me that it’s so cool to have these 30-minute dramas where it's tight, but it's also so much story that's packed into it at the same time. I don't think it was like that by design until we started getting into it and figuring out what is going to be the eventual length for these episodes. So much of that was when Chris would say, “Let's get through this" and then that scene would end up shrinking by 60%, which would then take the episode down five minutes overall, and you would realize that, “Wow, this really is a 30-minute episode with an hour’s worth of story.

NAUGLE: I would think the process of getting the cuts from 35 minutes to 29 minutes was impossible, but most of them, we got down to just around 30 minutes. That was a testament to Chris being able to kill his darlings a little bit and trust that the audience will get it. Sometimes we don't need the dialogue to explain it because we're achieving the feelings we want to feel without over-explaining things.

You mentioned the overlapping dialogue. Can you talk about editing those kinds of scenes? Was it recorded that way, and then you had to figure out the best way to get in and out of that or were those overlaps constructed in the edit?

EPSTEIN: It was much more the former as far as the editing goes. It was scripted as far as everyone knew what they were going to say, but to make it feel natural and chaotic to have six people yelling at each other simultaneously, you sometimes do lose words, and you sometimes do need to have stuff blended in on top of itself.

What I did a lot of was cutting mid-word on things to really be able to blend. So if the word is “outside," I would cut on the “t” of outside for one side of it as opposed to the end of a sentence, or end of a word, to really be able to blend one take to another. A lot of times, on the outgoing shot of a scene or the outgoing shot within a scene, I’d already be on the dialogue for the thing that I was cutting to.

I would be a frame or two off on that side, but with the speed and the noise, it doesn't make a difference. If everything was working smoothly, it would carry you through.

Joanna, any thoughts on those scenes?

NAUGLE: Oh yeah, when the first footage came in for the pilot, I thought, “Oh my gosh, how am I going to cut in between all of these words?” I would try finding the take that felt most appropriately paced, and I would use that as the backbone and then cut in as needed. I think on set, they were filming with the pace of the edit in mind. It wasn't like that was something we had to fabricate afterward.

We had so many background lines, throwaway comments, and jokes stacked in there that Chris said as long as we're getting the A-story, we are fine. If somebody re-watches it, maybe they will hear that. Marcus made this joke in the background in this scene, but the important part was that it should feel natural, like you're really in that kitchen. Maybe you caught what someone said, or maybe you didn't, but it should just feel like the room is full of these different voices. It should feel like a family-type organism, and everyone's playing their part and wisecracking or adding to the overall feeling of being in that place.

Is there any score at all, or is everything needle drop?

NAUGLE: There is a little bit of score. I know that there's one score we kept using which was this great track that our composer wrote for the opening nightmare scene in the pilot with the actual bear. I found myself using that over and over again, and then the composer tweaked it a little bit for later episodes. I feel like there were a couple of other moments of score in the background if there was music playing like it's supposed to be on the radio or something like that.

EPSTEIN: Yeah, not a lot of score, though when we did use it, it was great work from Jeffery “JQ” Qaiyum. I used two APM tracks on my episodes, and then after seeing the songs that we were able to use, I thought, "Why did I do that?” [laughs] The vast majority were either diegetic songs or needle drop specific. Being able to work with good music is fun. It was interesting. Those songs almost became a score to an extent when you're playing them out. It almost becomes reverse scoring to an extent. I tried a bunch of different songs for a scene initially, and then at some point, Chris and Josh were like, “Let's use this REM song as the end song.” So then I'd start to think about what within this song could I use, like a guitar solo or something. So you start working backward. It was the reverse scoring of making it fit within the beats of the song without it feeling forced into those, just as everything would connect naturally to where the music was moving, which is really fun, and lucky to be able to have a great piece of music to do that too.

Did you have to worry about the commercial breaks? Was that stuff scripted, or did it just fall where it fell?

NAUGLE: We basically decided very late where outbreaks would be, and I think Josh and Megan helped us out a lot with where to put them. We just cut as if it was one long thing and worried about it later.

EPSTEIN: We were both pretty much off the series once the commercial breaks were added. It's nothing that really affects anything, but there are a few moments where it’s noticeable, like where the music should play through the cut, but in the commercial edit, it stops and comes in hard.

NAUGLE: These are things that keep you up at night, right Adam? [laughs]

EPSTEIN: I know! I thought: “That’s not right!” [laughs]

What's the value to the production of having the editor at the mix?

EPSTEIN: We were all on all the mixes, and I usually get pretty detailed notes on the Frame postings. Having that kind of direct dialogue with the mixer and the sound designers is really beneficial.

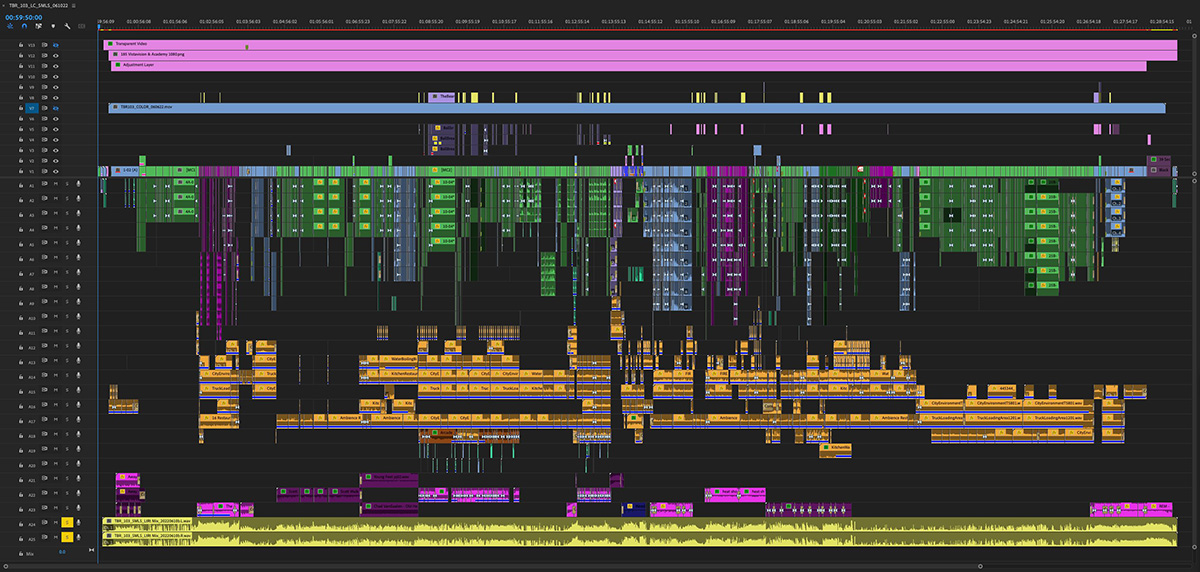

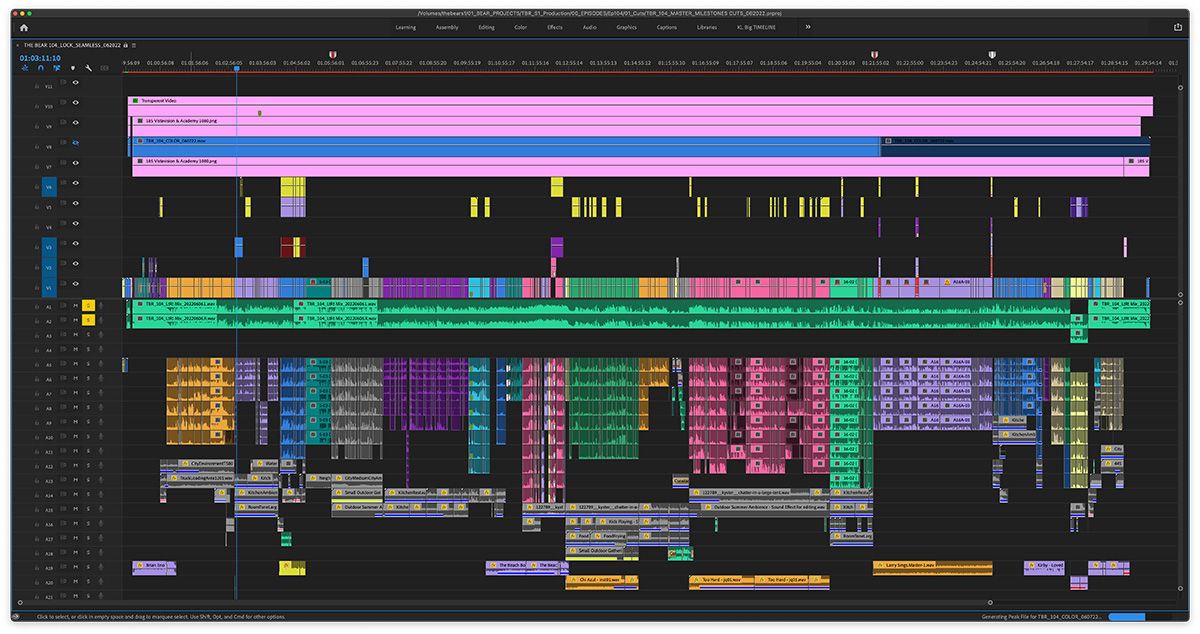

What were some of the ways that you two collaborated technically?

EPSTEIN: For internal cuts, we used Frame.io, and for external, we used Pix.

NAUGLE: We also used a program called LucidLink which was basically our cloud server, and it was essential to have that with all of us working remotely. I remember in the early pandemic, when we were all transitioning to working home, we had to make sure we downloaded the correct file and name it correctly — all had the same naming convention so that it would relink when we needed it to. It was brutal. You spent half the day just mirroring drives. So the fact that we could download a song when it was up there or export two minutes of a scene and say, “Here's the file path. Check it out when you have a moment," was great. It would've been impossible to make the deadline without that.

EPSTEIN: It was so helpful, especially in the instances where one of us would be very deep on an episode, and then we'd get a note or an idea, and I could add it. We're using Premiere with Productions, basically, which is very similar to traditional Avid shared media lock bins access — all that fun stuff. To have everything there at all times, especially with B-roll, especially with how much B-roll we had, to be able to see what other people were using to avoid redundancy was great. It would've been so much more cumbersome if we had to do it in a local storage way.

Were you editing with Premiere on your local machine with media that was in the cloud, and both of you had access? How were you accessing the Premiere Productions? Was that in the cloud as well?

EPSTEIN: Yeah, exactly. Going into almost year three of remote solutions, I’ve felt like I’ve done 15 different variations of remote workflow; for example, we used Jump Desktop on the show I did before The Bear, which lets you edit using a remote desktop. Our system for The Bear was a bit different since we had all the programs on our local machine and just the media in the cloud.

Any other thoughts on that, Joanna? Have you used other remote solutions that you liked or had considerations about?

NAUGLE: Yeah, I'm continuing to use Lucid on Ramy right now, and I think the assistant editors were doing some remote desktop stuff at Senior Post when they were doing two or three exports at once in a crunch.

Were there any rules or guidelines laid down about editing or the use of music or B-roll?

NAUGLE: Well, I got married in the middle of this season, and our friend Kelly Lyon came on like a total trooper to cover me for two weeks. She's such a fantastic editor and made the episodes better in the two weeks she had them, but in terms of hard and fast rules, we really wanted the music-driven montages to feel like a style of the show, but there's not necessarily a rule to them. I do feel like Chris would inject some thoughts about when we should go into a cooking music-driven montage, for example.

EPSTEIN: In a kind of cliché way, I feel so much of this show is a lot like cooking in the sense that you have guidelines as far as the things that you obviously can't do, such as burn something, but at the same time, so much of it is based on a feeling or a gut instinct at the moment. It's not necessarily “Oh, we did this because of this and this.” It's much more, “Oh, we did this because that felt right or interesting at the moment.” It’s a hard thing to codify and to put down in words. If someone said, “Here's the post-Bible on The Bear,” I don't really know what would go in it, truthfully.

There’s some fun crosscutting in that pilot episode. Can you speak to how that came about or what the process for that was like?

NAUGLE: We don't do a lot of crosscutting from outside stuff to food. That first opening montage is probably the craziest it gets in this season, and that's just introducing Chicago and Carmy, some baby photos. Just a bunch of information. One of my favorite crosscut moments in the season is in episode five, which Adam cut, when Sydney, Richie, Carmy, and Marcus are all spiraling out of control. They are in the same building, but they are clearly all so focused on different things that it almost could be anywhere. I feel like that just built to this moment, and then everything shuts down, showing that all these people are unaware of how the other one is impacting what's about to happen.

EPSTEIN: That sequence, in particular, is a testament to Chris, Josh, and Joanna Calo, who directed all the episodes that I cut, wrote a bunch of them and is one of the showrunners. We had these building blocks and then started to layer them on top of each other and ramp it up, knowing that your way out is gonna be the power hitting. You have a track, so you’re reverse scoring to get everything to that point where it's gonna hit. A lot going on in that scene.

One of the things that I loved in the show is a real subtle moment in episode four. They're eating together as a family, and everybody is eating this cake. The episode ends on this lovely exhale, and I thought that it just said so much about the character.

EPSTEIN: Definitely.

NAUGLE: Totally, I love that scene. Liza, who plays Tina, is one of my favorite characters on the show, and it was the perfect time for her to have this moment of coming to terms with Sydney. Up to this point, we get her shtick, she doesn't want to do it, but then with that episode, I believe so much in her performance that she's had this change of heart and sees Sydney with respect for the first time. For so long, you see her hold in so much anger and frustration to end with her exhausted and eating this beautiful cake with her feet killing her. She's finally come to terms with the current situation. It just feels like a happy ending, even though I wouldn't call her happy at that moment, but there is something nice about the progress being made and seeing these people come together.

The actors know their arcs, and they know what they're trying to accomplish to get themselves to a new place. How much of that are you trying to orchestrate as an editor? How often are you saying, “She needs to be less angry here? She needs to be angrier here. She needs to be less defensive here.” Can you talk about sculpting that performance?

NAUGLE: I think that's one of my favorite parts about editing TV is that you have all these hours to go on a journey with these characters. All of these performances were so strong, and the characters were so well written that it was so fun to track them over the course of the season. I think my favorite arc to be invested in is Marcus. He has all this potential. He's self-taught but made mistakes but wants to keep growing. I feel all the characters go on their arc, and because they're such a great ensemble, you really want to see these people aren't remaining stagnant, and you want to make sure that we're checking in with all of them enough. It’s not just Carmy’s story. Everybody is changing as a result of this new leadership coming in.

EPSTEIN: When you have great writing and great actors, you want kind of get out of the way of it a little bit. It was really cool to see characters like Tina or Richie, who people might initially hate. They might think, “They should fire them immediately. They're the fucking worst!” But your response to them is “Sure, but keep watching” and then you see the response at the end is “Oh my God, Tina, I love her so much!”

It’s written in such a strong way without deliberate handholding, with a natural evolution with great actors. I think when you're presented with something like that, it's my job to kind of get out of the way of something good. I feel lucky that I don't have to make something that doesn't exist.

This is on the page, this arc is there, and this actor is just nailing it, and I get to let them do that.

There were a couple of moments with Tina where we had discussions about how many times we see her take a bite into something and be like, “Oh my God, this brings back these memories. This is amazing.” We discussed if that was a little too on the nose or a little too much, but then we’re like, “No, she's great!”

I think it's having faith that when you're so in the weeds on making something when you have seen the same scenes 30 or 40 times that something might come across as a little melodramatic but have to remember what it’s like seeing this for the first time? What’s the impact of that? That’s when you default to having faith in the actor and faith in the story and let it be what it is.

Is there anything else you feel like you want to talk about?

EPSTEIN: I do think one of the reasons that the show has broken through in whatever way that means nowadays is because it reminded me of “team filmmaking” in the sense that you're only as good as every component of what you have. If you have a great writer, but the DP doesn't do a good job, then the final project is not gonna be good. You can apply that to literally every aspect of production and post-production.

I think a lot of people, even if they've never worked in a kitchen, can see those similar values of struggle and helping each other, being honest about your emotions, and how greatness can really only come from people coming together and working towards a goal and strengthening each other. I think that helps it resonate truthfully.

I love that. It was wonderful to talk to both of you.

NAUGLE: Thank you so much, Steve. This was a lot of fun to relive the post process.

EPSTEIN: Yes, Steve, Thanks so much!